The Government released a gender pension gap briefing paper earlier this month, that examined the disparity between the retirement outcomes for men and women. Stowe Partner Matthew Taylor looks at the causes of the gender pension gap and whether divorce can address the inequality.

Divorce and the Gender Pension Gap

Despite more than 50 years having passed since the Equal Pay Act 1970 came into force, it is well-known that there remains a significant difference in the earnings of men and women. In fact, the Office of National Statistics calculated a 15.4% pay gap between the genders. What is less frequently highlighted is the impact this has on the pension assets of men and women, with the gender pension gap standing at around 37.9% in 2019-20 , according to research from the trade union Prospect.

The 3 pension gap factors

The government briefing paper The Gender Pension Gap (4 April 2022) cites 3 key factors that create such a stark difference in pension assets held by both genders:

- Women are more likely to be out of work or be in part-time employment than men. This leads to a lack of pension contributions. The biggest reason for this is the greater likelihood that women will provide unpaid care to children and elderly relatives.

- Demographic differences resulting in greater life expectancy for women than men mean that they need income in retirement for a longer period, requiring a greater initial fund to produce the same income as men.

- To qualify for an auto-enrolment employer’s pension, an employee needs to earn at least £10,000. As women are more likely to be lower earners or work second jobs, they are less likely to qualify.

Addressing the imbalance

To address this imbalance the paper proposed 3 reforms, each addressing a cause of the gender pension gap:

- Provision of affordable childcare for pre-school age children

- Make pension rights a compulsory part of divorce proceedings

- Reduce the earnings trigger under automatic enrolment in a workplace pension as more women than men tend to be excluded from this policy by the earnings trigger.

The pension divide

With women starting from a lower base in respect of pension provision, it might be expected that divorce would act as a corrective to this inequality, with more women than men likely to be entitled to a share of their spouse’s pension on divorce. However, this is not the case. The reality is that divorce exacerbates these inequalities. A 2021 study by the University of Manchester looking at the pension provision for divorcees age 55-64 found that men had an average total private pension fund value of £100,000, whereas women had accrued just £19,000. So why is this the case?

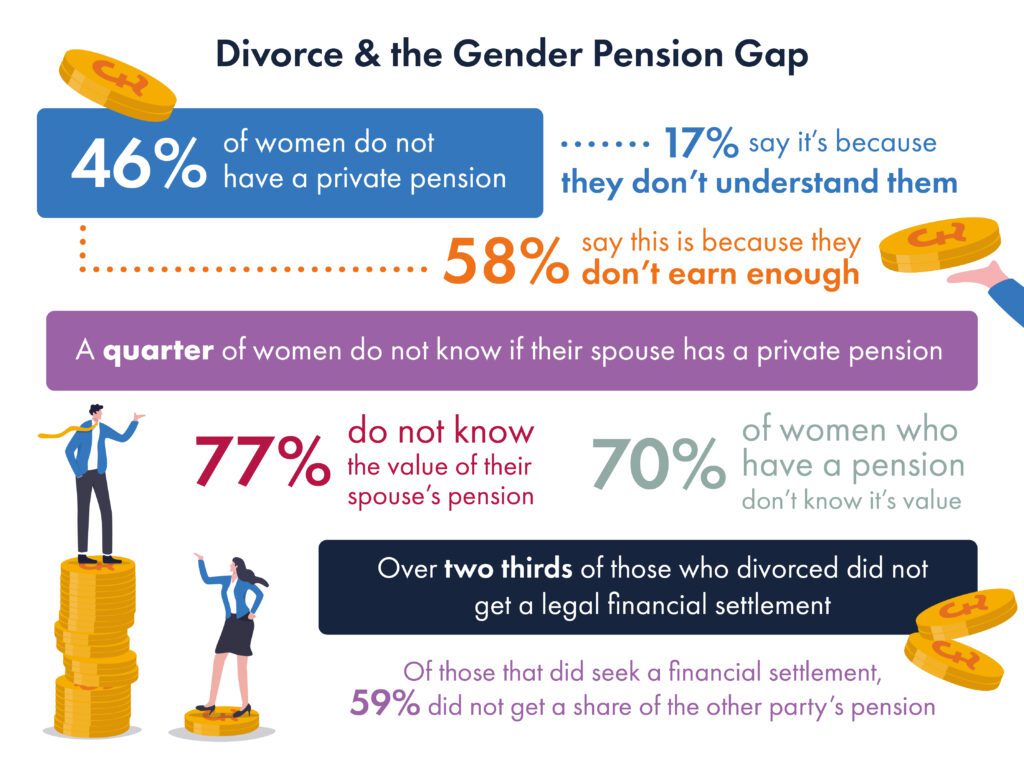

A recent study* conducted by Stowe, designed to understand and help address the increasing imbalance in the UK’s gender pensions gap, revealed that 46% of women have no private pension at all, with 58% saying this is because they don’t earn enough, while 17% say it’s because they don’t understand them. Among women who do have a pension, 70% do not know their pension value.

Pension Sharing Orders

Pension sharing orders are the exception rather than the rule on divorce. Financial orders of any kind are only made in around 1 in 3 divorces. Of those cases where financial orders are made, only around 12% include pension sharing orders. With around 100,000 divorces of opposite-sex couples in the UK each year, this means that only around 4,000 people are benefiting from a pension sharing order.

Pensions and divorce

There are a variety of reasons why this is the case. Pensions are often ignored or forgotten on divorce, particularly where parties do not have legal representation. They are also complicated, and many people do not appreciate the true value of their pensions. That is particularly the case when defined benefit pensions – such as public sector schemes with the Armed Forces, local government, or NHS – are involved, as the headline figure for the value of those pensions used in divorce proceedings (known as the CE or Cash Equivalent) will often not accurately reflect their true value which is frequently far greater than the CE indicates.

Our study showed that a quarter of women do not know if their spouse has a private pension. Furthermore, 77% of women surveyed do not know the value of their spouse’s pension.

Pension Offsetting

In many divorces, pensions are not dealt with by way of a pension sharing order but by an approach known as offsetting, where one of the parties will retain a greater share of another asset in lieu of a pension share. Commonly, this will involve a party retaining the family home instead of receiving any interest in their spouse’s pension. Anecdotally, it is far more common for a wife to elect to do this rather than a husband, not least because they are more likely to be the primary carer of the children and want to retain the home for their stability and security.

Pension rights in divorce

The Gender Pension Gap briefing paper recommends that the government considers changing the law to ensure that pension rights have to be considered by the court in any divorce; not just those where a financial order is applied for. Additionally, the paper recommends that the pension sharing process should be streamlined to reduce delay in implementing any sharing order.

Narrowing the gender pension gap

With the advent of no-fault divorce and the perception that divorce has become easier as a result, there is a risk that divorcing spouses may consider that dealing with complex and time-consuming matters such as pensions is not necessary. This can have disastrous consequences for women later in life and anything that can be done to ensure that people are aware of their rights to pensions on divorce is to be welcomed.

Get in touch

For more information about Pensions Sharing Orders, Pension Offsetting or Financial Orders in divorce, please do get in touch with our Client Services Team using the details below or make an online enquiry

Useful Links

Divorce and the gender pensions gap FT article

* Stowe Family Law conducted a pension survey polling 400 women aged 35 – 64 around the UK, designed to understand and help address the increasing imbalance in the UK’s gender pensions gap.

Thanks for the sharing.. very useful information

Often the disparity is because the weaker financial party gets more of the current assets, often in the form of more equity in the house. Presumably the review considered the option to the weaker financial parties to downsize and release equity to buy a pension? Or is this going to be yet another tipping of the scales in favour of the weaker financial party with no consideration whatsoever given to where they would have been had they not been married? Will they now get 90%+ of the home equity “because they need it” and more than half the pension too because they “can’t save as much?”

Of course, in divorce law, because I paid into my pension and my wife chose to opt out and spent the money on shoes and affairs instead, it’s only right she gets half of mine.

I am about to attend my first Financial hearing at court. Do I need a barrister to represent me, if the first hearing is just a discussion to encourage resolution of the assets?